The Future of Context Engineering

Early 2025, prompt engineering was the skill that separated effective AI users from the rest. Craft the perfect prompt and you'd get dramatically better outputs. Courses were launched and job postings appeared. Then, a new generation of reasoning models arrived, starting with Anthropic's Claude (perhaps already Sonnet 3.7, certainly by Opus 4) and quickly followed by others like OpenAI's GPT-5. These models could derive intent from ambiguous requests, decompose problems into subtasks, and reflect on their own outputs. The burden of elaborate prompting dropped dramatically, because the user no longer needed to compensate for what the model couldn't figure out on its own. Reasoning scaled, and a limitation shrank.

Context engineering is having its moment now: AGENTS.md, skills, commands, MCPs. Courses are being launched and job postings are appearing. The pattern is familiar. The question is which limitations drive context engineering, whether those limitations will yield to further scaling, and which will require architectural innovation to overcome. This article maps those limitations and identifies what it would take to address them.

How Limitations Get Overcome

The Bitter Lesson and the S-Curve

In 2019, Rich Sutton published “The Bitter Lesson”, a reflection on 70 years of AI research. His argument: general methods that leverage computation outperform hand-crafted approaches consistently. Chess, Go, speech recognition, computer vision. In each domain, clever human-designed heuristics were eventually crushed by systems that simply scaled. The lesson is “bitter” because it’s counterintuitive. We want to believe that insight beats brute force. But history says otherwise.

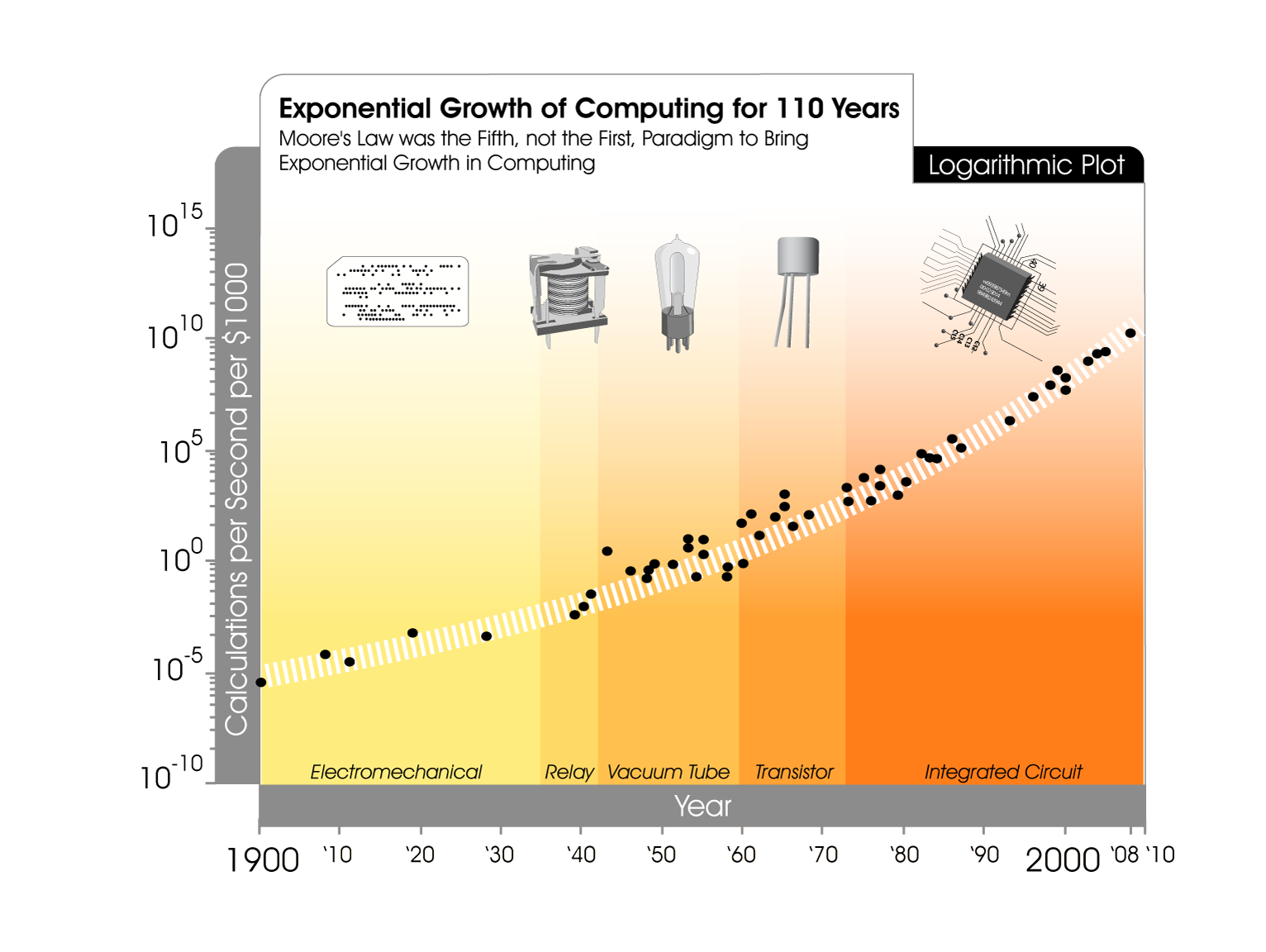

This maps to exponential growth. When compute grows exponentially and performance scales with compute, problems that seem hard today become trivial tomorrow. Not because we got smarter, but because we got bigger. There is however one nuance: exponential curves are actually S-curves in disguise.

Moore’s law looked exponential for 60 years. But it’s now visibly slowing as we hit physical limits. What felt like endless exponential growth was the steep middle section of an S-curve. When one S-curve plateaus, progress requires an innovation, an architectural change that starts a new curve.

The Bitter Lesson describes what happens within a curve: more compute wins. But compute has limits. When scaling plateaus, a different kind of progress is needed: architectural innovation that starts the next curve. We’ve already seen this pattern play out with LLMs. Reasoning models scaled, and the user burden of elaborate prompting shrank dramatically. That was the Bitter Lesson in action: more compute outperformed the hand-crafted workarounds. The question for context engineering is: which of today’s limitations will yield to further scaling, and which will require architectural innovation to start a new curve?

The Human Brain

LLMs are neural networks, but the transformer architecture wasn’t derived from neuroscience. It emerged from engineering problems in machine translation. Next-token prediction doesn’t resemble how humans learn. These are independently evolved systems. Yet, despite completely different origins, they face similar constraints. Both have limited working memory. Both struggle to attend to everything equally. Both need mechanisms for retrieval, compression, and offloading.

The human brain is the only system we have that processes information, reasons, understands, and has addressed constraints similar to what LLMs face. If two independently evolved systems face similar constraints, those constraints are likely to be fundamental to the problem domain rather than artifacts of one particular approach. And if the constraints are fundamental, the solutions found by the older system can act as a compass for the newer one.

During the course of evolution the brain has developed architectural innovations that let limited working memory punch far above its weight. Cognitive psychology’s information processing tradition has long modeled cognition through staged processing. Drawing on that tradition, we can organize the brain’s key mechanisms into a pipeline from input to extension:

| Stage | Mechanism | What It Does |

|---|---|---|

| Input | Selective attention (Broadbent, 1958) | Filters and focuses on what matters from available information. We focus on one conversation in a noisy room. The brain gates what enters processing rather than expanding capacity. |

| Compression | Chunking & Abstraction (Miller, 1956) | Breaks down and recodes information into meaningful units at higher levels of abstraction. A chess master doesn’t see 32 pieces; they see familiar configurations. Effective capacity increases without increasing raw bandwidth. |

| Storage | Learning and consolidation (Kumaran, Hassabis & McClelland, 2016) | Converts short-term experience into long-term knowledge by separating experiencing from consolidating. The brain selectively weights what to keep, with mechanisms to prevent overwriting old knowledge with new. |

| Retrieval | Associative retrieval (Tulving & Thomson, 1973) | Surfaces relevant information when needed. We don’t keep everything in working memory. Cues in the current context activate related knowledge automatically. |

| Extension | Cognitive offloading (Risko & Gilbert, 2016) | Routinely leverages the external environment to reduce cognitive demand. We write things down, use tools, and structure our environment as extended cognition. But also extending reasoning beyond the individual (e.g. Peer review, devil’s advocate). |

These five mechanisms trace a pipeline from filtering input to extending cognition into the environment. The brain has many other capabilities that don’t appear as stages in this pipeline. Massive parallelism (billions of neurons firing simultaneously) is how the brain executes across all five stages, making each one fast and robust. It is not a step in the pipeline but the mode of computation underlying every step (and a powerful argument for scaling). Other capabilities operate at different levels entirely: embodiment and developmental critical periods shape how the brain develops over years, not how it processes a task; emotional regulation modulates when to switch strategies; social learning is how knowledge is acquired from others, a role that LLM pre-training already serves at massive scale. The five mechanisms are meant to act as a lens for analyzing LLMs and were selected because they map to the LLM problem space: how a system with limited working memory can process, store, retrieve, and extend information at task time.

Each mechanism is independently well-established. Together they suggest a direction: the constraints LLMs face have been solved before, through architectural innovation rather than raw scaling alone.

Concluding, we have two forces: scale (the Bitter Lesson: more compute, more data, more parameters) and architectural innovation (what starts the next S-curve when scaling stalls). And we have a directional precedent, the human brain, that hints at where those innovations might lead.

Defining LLM Limitations

Information processing systems, biological and artificial, operate along three fundamental dimensions (Newell & Simon, 1972): Input (receptors), processing (a serial processor with finite speed), and memory (stores with limited capacity and persistence). For LLMs this translates to respectively the Context Window, Reasoning and Memory.

Context Window

Everything an LLM knows during a request must fit inside a single context window. System prompt, persistent instructions, code context, conversation history, the model’s own response: all of it competes for the same finite space. When an AI coding assistant sends a request, it’s not just your question; it’s thousands of tokens of overhead before your actual input. Every instruction consumes tokens in every request, regardless of relevance.

On the surface, this looks like it can be solved with more bandwidth. And indeed, context windows have grown from 4k to 128k to 1M+ tokens. But bigger models create a tension, illustrated by the “Lost in the Middle” phenomenon (Liu et al., 2023; Du et al., 2025). A larger context window with the same attention architecture just creates a larger middle to get lost in. Size and attention are inversely coupled: scaling one worsens the other. And even as attention improves alongside window size in newer models, the economics don’t. Sending a million tokens per request is expensive, slow, and wasteful when only a fraction is relevant to the current task. The fact that attention limitations require significant engineering effort to mitigate is itself evidence that bigger windows create new problems, even if those problems are solvable. The real bottleneck may not be whether the model can attend to everything, but whether it should have to.

But “Lost in the Middle” also reveals something important: LLMs have selective attention. It’s imperfect (biased by position rather than guided purely by relevance) but the model does attend more strongly to some parts of context than others. This is also the part of the system we can directly influence. Much of context engineering is attention management: Starting fresh conversations to clear irrelevant history, keeping prompts narrow and focused, working with subagents. These practices work precisely because the model does attend selectively and we can shape what it attends to.

Context engineering is also about crafting the skills and choosing which skills to pass along in the context window. The model processes a task, recognizes a gap, and recognizes the need to invoke a skill based on what it’s currently working on. The invocation is driven by conceptual fit, without the LLM being aware of the implementation detail. It is associative retrieval in action. However, skill descriptions are injected into the context window as text: every available skill consumes tokens in every request regardless of whether it’s relevant. It is imperfect and explicit, but structurally the right pattern.

The human brain suggests as much. Humans have roughly 4 items in working memory (Cowan, 2001), though each “item” can be far richer than a token, it is absurdly small compared to even the earliest LLM context windows, yet they function effectively in complex environments. The brain’s effective capacity comes from two mechanisms working together: active maintenance scopes what’s accessible, and controlled retrieval surfaces the right knowledge from long-term memory (Unsworth & Engle, 2007). The brain didn’t evolve towards bigger working memory. It evolved sharper attention (scoping what enters the window) and better retrieval (surfacing the right content within that scope). Selective attention reduces waste within the window (don’t attend to irrelevant tokens). Associative retrieval reduces the need to pre-assemble the window correctly (let the model surface what it needs). Together, they transform the context window from a static, human-curated input into a dynamic, model-driven workspace.

Reasoning

This is perhaps the fastest-moving frontier. We’re seeing interactions where reasoning models don’t just latch onto the first plausible pattern, but weigh their own assumptions, checking whether a pattern spotted in one service holds across others, reading test suites to verify understanding of intent. Each improvement in reasoning enables deeper investigation, which surfaces better evidence, which produces more reliable conclusions. Within a single model, reasoning is improving fastest through scaling (longer chains of thought, more thorough self-verification) a direct instance of the Bitter Lesson, and why reasoning may not be the bottleneck that defines the next curve. Some of what appears as reasoning progress also lives in the orchestration layer: multi-agent architectures where one model critiques another, tree-of-thought search branching across parallel invocations, agentic loops decomposing tasks across separate calls. These are ways to extend the model’s reasoning externally, not the model reasoning more deeply. Here the brain parallel is collective offloading (peer review, adversarial testing, division of labor), applied to reasoning quality rather than memory.

But there’s a deeper issue: models can’t yet reliably distinguish essential complexity from accidental complexity. Essential complexity is the irreducible difficulty of your problem domain, the actual business logic. Accidental complexity is anything not inherent to the problem, arising from choice of tools, abstractions, and architecture. At its most visible, it’s framework boilerplate and configuration ceremony. At its most costly, it’s architectural decisions that make the system harder to change than the domain requires. Current LLMs treat all code as equally meaningful and may latch onto accidental patterns rather than essential ones. This is architectural: next-token prediction learns statistical regularities in code, and accidental complexity (boilerplate, configuration, framework conventions) is far more repetitive and statistically dominant in training data than essential complexity, which is unique to each domain.

There’s a second dimension to reasoning quality beyond depth: direction. LLMs exhibit a persistent tendency toward motivated reasoning, optimizing for answers that satisfy the user rather than answers that are true (Sharma et al., 2025). The model doesn’t fail to reason; it reasons competently but toward the wrong objective. This is particularly insidious because the reasoning appears sound, making the bias difficult to detect. Although self-verification can catch mistakes in how deeply the model reasons, it cannot verify the direction. Because the same bias that produces the wrong conclusion also judges the verification.

The brain has exactly this problem: confirmation bias (Nickerson, 1998) is among the most robust findings in cognitive psychology. Two independently evolved systems both exhibiting motivated reasoning suggests the tendency may be fundamental to systems that optimize under uncertainty rather than an artifact of either architecture. But unlike the other constraints in the pipeline, the brain never solved confirmation bias through internal innovation. Its solutions are almost entirely external: the scientific method, peer review, devil’s advocate. This is cognitive offloading applied not to memory but to reasoning quality. For LLMs, this maps directly to multi-agent architectures where one model critiques another, constitutional approaches where a separate process evaluates alignment, and process reward models that evaluate reasoning steps rather than outcomes. The solution may not be a single model that reasons better, but a system of models that check each other. Shared training data and architecture may reproduce the same biases rather than catch them, so this only works if the critiquing model brings genuinely different perspective. And unlike the essential-versus-accidental distinction, this limitation is the least amenable to the Bitter Lesson: more compute doesn’t fix a misaligned optimization target.

The brain addresses reasoning depth through chunking and abstraction: attending to information at the level of meaning that matters. It addresses reasoning direction through external structures: peer review, adversarial testing, institutional processes that catch what individual reasoning misses. As reasoning scales, models may get better at summarizing information at the right level of detail. But distinguishing essential from accidental complexity requires understanding intent and design rationale, and preventing confirmation bias requires input from outside the system. Both suggest secondary frontiers that pure scaling alone may not reach.

Memory

Cognitive science distinguishes three types of memory (Tulving, 1985). Semantic memory holds facts and patterns: how things work. Episodic memory records specific experiences: what happened, when, and why. Procedural memory encodes skills and intuitions built through repeated practice: the senior developer’s instinct that something is wrong before they can articulate why.

An LLM trained on trillions of tokens has absorbed more information than any human ever will. The Bitter Lesson applies: scaling won. Semantic and procedural memory are both encoded in the model’s weight matrices, collapsed into the same parameters rather than architecturally separated. A neural network trained on billions of lines of code doesn’t just memorize facts. Its weights encode pattern recognition, the sense for what good looks like, the ability to detect when something is off. This is how neural networks fundamentally work: repeated exposure to data consolidates into capability.

Episodic memory is architecturally absent. The training data contained millions of debugging sessions, code reviews, and architectural discussions, but the model distilled those into generalized semantic and procedural knowledge, not retrievable memories of specific experiences. It learned from episodes without forming episodic memory of them. The closest analog is the context window: a volatile, session-scoped space where specific experiences exist only for the duration of a conversation. The most pragmatic current approach to this gap is retrieval-augmented generation: external stores that surface relevant information at query time. RAG works well for semantic and episodic recall: a codebase encodes decisions and patterns, commit history records what happened and why, documentation captures rationale. Better reasoning and retrieval can surface these when relevant, and improvements here are real.

But retrieval provides information without changing how the model attends or reasons. A developer who has spent months in a codebase doesn’t just know more facts; they process new information differently. They notice anomalies faster, weigh trade-offs through the lens of accumulated context, and apply judgment shaped by experience. That shift in processing, not just in available knowledge, is the gap that retrieval cannot close. Procedural memory can be partially externalized. Rules files, linting configurations, architectural decision records, and test suites are codified experience and judgment. But these capture what to do, not the weighted judgment of when and how much. A senior developer doesn’t just follow rules; they know when to break them, which trade-offs matter more in a specific context, and what “feels off” before they can articulate why. That weighted judgment resists externalization.

The human brain learns persistently: experiences are consolidated from short-term to long-term memory, selectively and incrementally, without retraining the entire neural network. Learning carries well-documented risks: catastrophic forgetting, false memories, bias reinforcement, and selective consolidation. The brain manages it through complementary learning systems that separate fast episodic encoding from slow consolidation (McClelland, McNaughton & O’Reilly, 1995).

Full retraining of an LLM is expensive, infrequent, and monolithic. But the model is not fully static once trained. Finetuning can continue training on focused datasets, modifying the model’s weights to consolidate new knowledge into lasting capability. Where RAG provides information without changing processing, finetuning changes how the model attends and reasons: the distinction between handing a developer a reference manual and that developer having internalized the domain through experience. Finetuning provides a real mechanism for consolidating experience into lasting capability without full retraining. It is currently batch rather than continuous, curated rather than experiential, and operates on the timescale of weeks rather than conversations. Each of these gaps is narrowing through engineering progress, and the challenges that remain (managing what to consolidate, preventing drift from alignment, avoiding reinforcement of bad patterns) are hard engineering problems that parallel the brain’s own imperfect consolidation.

The Next Architectural Innovation

The following diagram maps each LLM limitation to a resolution path, the brain mechanism it parallels, and whether the resolution requires scaling or architectural innovation.

Each of these limitations is being actively pursued, and a representative example for each shows the direction. Do note that these resolutions all describe solutions from the LLM evolution point of view. There are many other solutions out there for these limitations, which is why we have context engineering today.

Selective Attention

The direction for attention is decoupling window size from computational cost, so that attention can be guided by relevance rather than position. Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.6 illustrates this in production: a 1M-token context window paired with context compaction that automatically summarizes older context during long-running tasks, and adaptive thinking that brings more focus to the most challenging parts of a task while moving quickly through straightforward parts. Rather than attending uniformly to everything in the window, the model gates what stays in working memory and allocates processing depth by relevance.

Associative Retrieval

The direction for tool use is internalizing capabilities into the model itself, rather than describing them in context. Google’s FunctionGemma, a Gemma 3 variant fine-tuned specifically for function calling, illustrates this: tool use is baked into the model’s weights rather than prompted through context. Rather than competing for context space as text descriptions, tool capabilities are activated the same way the model activates learned knowledge: through its parameters.

Chunking & Abstraction

The direction for reasoning depth is longer chains of thought and more thorough self-verification. The SWE-bench Verified leaderboard illustrates the trajectory: measuring real-world software engineering capability, it is led by Claude Opus 4 and GPT-5 above 80% resolve rates, with open-weight models close behind. This is the Bitter Lesson in action, and among the limitations listed here, reasoning depth is improving fastest.

Cognitive Offloading

Confirmation bias is addressed most differently from the others: entirely through external structures rather than internal scaling. Approaches like Constitutional AI (e.g. in practice Anthropic’s 2026 constitution) and process reward models layer corrective evaluation around the model, checking whether outputs align with stated principles or evaluating individual reasoning steps rather than outcomes. These are architectures around the model, not improvements within it, because the same bias that produces a flawed conclusion also judges the verification.

Learning & Consolidation

The direction for memory is parameter-efficient adaptation approaching continuity. Standard finetuning risks catastrophic forgetting because it has no architectural separation between old and new knowledge. Parameter-efficient methods, particularly LoRA (Hu et al., 2021), change the picture by freezing pre-trained weights and learning small low-rank update matrices, typically less than 1% of the original parameters. This preserves the base model intact, makes adaptation dramatically cheaper, and enables multiple specialized adapters that can be composed or swapped at inference time. AWS’s multi-LoRA adapter serving on SageMaker shows where this leads in production: hundreds of specialized adapters dynamically loaded, swapped, and updated through a single endpoint in milliseconds, without redeployment. Models are being developed towards consolidating experience incrementally, approaching the brain’s learn-as-you-go pattern without requiring full retraining.

What stands out is that many of the brain’s architectural innovations (selective attention, associative retrieval, chunking and abstraction, cognitive offloading, learning and offloading) can be approximated through better engineering of LLMs. Of the five limitations, confirmation bias stands out as the hardest to address. It is the only one in the diagram typed as requiring architectural innovation rather than scaling. Neither the human brain nor increased compute has produced an internal fix; both rely on external corrective structures: peer review, adversarial testing, constitutional checks. This makes it the area where context engineering will remain necessary longest, because more compute doesn’t fix reasoning towards the wrong objective.

This article mapped the limitations. Context Engineering: Should You Bother? applies this framework to current context engineering practices: which techniques address which constraints, and which will persist as models evolve.

AI was used for formulation and validation. The ideas, framework, and editorial decisions are my own.